We once spoke to Arthur Harding, about the chances of Wales against the New Zealanders. "We'll win if Gwyn is with us. You don't know what it is, man, to have him behind you."

A Welsh International in many tough, struggles with Nicholls said of him recently:

"Do you know Gwyn? He is the best man breathing."

Evening Express. 23rd February 1907.

Gwyn Nicholls nearly didn't play against the 1905 All Blacks. He might have stayed in Australia in 1899 after the tour which first established him as a global rugby star. Rumour had it that he'd turned his back on Cardiff and Wales by accepting a position with a bank in Brisbane. Another story had him marrying a wealthy heiress and becoming part of a wool stapling business.

He had been due to return to Wales to take up his rightful role as Cardiff captain that autumn. October came and went. There was still no sign of Nicholls. People in Cardiff were quietly beginning to panic.

Cardiff, without Gwyn Nichols, is like the play of "Hamlet" with the prince left out, i.e. not worth much.

South Wales Daily Post. 14th October 1899.

When he finally returned, on 13th of January 1900, a crowd of hundreds met him at Cardiff Central Station and stormed onto his train as it pulled in. Nicholls slipped away through the crowd but was spotted. The horse drawn cab carrying him and his friends (including Bert Winfield, the Cardiff fullback and Gwyn's business partner) was stopped and the horses uncoupled. 50 admirers then took hold of the cab and hauled it down Westgate Street to the cheers of passers-by. They arrived at the Grand Hotel opposite the Arms Park where Gwyn's brother Sydney was the proprietor.

Two days later, a reporter from the Western Mail managed to pigeonhole him at the Grand.

"Where have you been all this time?"

"Well, I stayed a week in Queensland, and afterwards went up north country to a large cattle station, where I had good deal of rough riding, and some experience of cattle ranching."

"You were sorry to come back again?"

"Yes, in one sense; I made as many friends out there as I have in Wales."

"Do you intend going back?"

"No; not at present. I should go back if I could, but there's no chance. I should like to go back immensely."

The Western Mail. 15th January 1900.

Nicholls then had found a chance for adventure and taken it. The open spaces and opportunities of Australia must have had huge appeal for a young man and natural athlete. A man who, in a sense, was already an immigrant. His family were from West Country English farming stock and had moved to Wales when Gwyn was a child. Rough riding in Queensland must have felt like a natural extension of the journey his life had already taken him on. Returning to Wales had clearly been a difficult decision. His friend Charlie Adamson, the other star of the tour, had indeed accepted a position and stayed on in Australia.

Like Adamson, Nicholls was adored in Australia. That 1899 tour had made them into some of the first global rugby superstars.

Mail advices received this morning from Australia state that Gwyn Nicholls, the international three-quarter, has obtained widespread popularity in the Colonies. His play has not only delighted the spectators, but his general demeanour on the field has been everywhere admired.

Evening Express. 20th September 1899.

Of the three-quarters, Gwyn Nicholls has almost throughout been the shining star-in fact, I should not be erring if I stated that his play has caused little less than a sensation over here. Equally at home both in defence and attack, he has all along played a most unselfish game, on several occasions without the least hesitation, handing over the ball with the line perhaps at his very mercy.

South Wales Daily News. 10th October 1899

Perhaps it was a sense of duty that compelled Nicholls to finally return. Or perhaps a sense that there was business left unfinished. Financially, socially and in terms of lifestyle, staying in Australia would have made sense. But there would have been no more Wales caps. And no more opportunities to captain Cardiff. No more Cardiff Arms Park. Perhaps the 26 year old knew that the game had more in store for him.

Nicholls had been born in Westbury, Gloucestershire in 1874. He moved to Cardiff with his family at a young age. It was an athletic, farming family. His older brother Sydney joined Cardiff rugby club in 1886 when Gwyn was 12, and was still playing rugby professionally for Hull in 1910 at the age of 42.

Sydney’s first season at Cardiff was the season Frank Hancock’s innovation of the four three quarter system and “passing game” had brought the club an (almost) invincible season during which they’d swept all before them and changed the game forever. The “scientific game” and the art of drawing men before passing would become the style of rugby Gwyn would become devoted to.

Gwyn himself started out playing as a teenager for Cardiff Star and Cardiff Quins, playing in the intense local competitions that took over the city in the years following the explosion of interest in the game. He made his debut for Cardiff in 1893 but with so much talent at the club, didn’t establish himself until 1894/95.

By the time he was 22, he was a Welsh international, making his debut against Scotland.

Gwyn Nicholls, who partners Arthur Gould at centre three-quarter, is a youngster who makes his debut on the international football field today. He is a brilliant individual player, and has a happy knack of utilising any stray openings that present themselves to excellent effect. There is great joy in Cardiff over his selection...

South Wales Daily Post. 25th January 1896

It was fitting that he made his debut alongside “Monkey” Gould of Newport. Gould was the first superstar of Welsh rugby and the first man to be called “The prince of centres”. Nicholls would become the second.

In this early part of his career, Nicholls formed a close partnership with the winger Viv Huzzey, for both club and country. Huzzey would benefit hugely from the space created by Nicholls who was evolving from a talented runner and tackler into a master tactician. Huzzey would average twenty tries a season while playing alongside Nicholls.

Few better expositions of the modern scientific passing game have been given in London than was displayed by the Cardiff back division. If there was one man more than another to whom Cardiff owed their victory it was undoubtedly the international centre, E. G Nicholls, the pivot upon which the whole back machinery worked. Both in defence and in attack he was the most prominent man on the side, and it was in a great measure through his judgment that Huzzey, on the wing, was provided with so many opportunities of scoring.

Daily Mail. December 1898.

By 1898, Nicholls was Cardiff club captain. He would retain it three years running, although in the third he had attempted to pass on the responsibility to his friend Huzzey. Overruled by the club’s members, Huzzey then left Cardiff for rugby league, where clubs soon hoped to reacquaint the famous double act.

During Monday rumour was busy coupling Gwyn Nicholls, the Cardiff captain, with Huzzey. An offer of £400 -far and away the biggest ever made by a Northern Union club- is said to have been the bait for the prince of centre three-quarters, and certain professed emissaries from the Oldham Club seem confident that they will be able to secure the Welsh international. Evidently the Oldham people now recognise that they have not secured a wonderful right wing player, and that Huzzey is of little comparative merit when playing without Nicholls.

South Wales Daily News. October 1900.

Rumours of even bigger inducements to go north were reported. It was said that £1,000 (adjusted for inflation this would today be a six figure sum) had been offered to Nicholls by at least one club. But his position as a manager at the Grand Hotel gave him the financial security to not need the money. Apart from a brief stay in Newport while starting a business there, he would stay loyal to Cardiff for his whole career.

After that triumphant return from Australia, Nicholls had gone straight back into the Wales team for their game against Scotland. He scored a try in that game and also played in the next game against Ireland to seal Wales’s second ever championship. Now 26 he had begun to approach the peak of his powers. This was the year he began to be called the Prince of Three-quarters.

The game showed one thing plainly, and that is that as a centre three-quarter Gwyn Nicholls still has no superior at the present day, and while they have such a grand player in their team Cardiff will always be a formidable side. His was the mind which directed the attack, and the skill and precision with which the movements were carried out were due to the masterly way in which be handled his team. Cecil Biggs, who played on Nicholls's wing, had a most enjoyable afternoon...

The Daily Mail. December 1900.

Nicholls was not simply a graceful attacker but the mastermind of the back divisions he played in. His value to teams was not simply his solid defence and inspired play with the ball but his rugby brain and, as he grew more and more experienced, his leadership. By 1902, Nicholls was captain of Wales and led his country to a third championship.

In 1904, Nicholls had chosen to retire. He was set to be married and it was time to settle down. Not only that, in the past year and a half he had begun acquiring injuries at an alarming rate.

Within sixteen months he has been injured four times, and thus prevented playing in four inter- national matches. First of all he had his collar-bone broken at Blackheath, then he was badly damaged on the knee at Llanelly, then he had slight concussion of the brain, and, finally, he had to retire with a broken rib.

Evening Express. 9th April 1904.

In 1904 had had finally relinquished the Cardiff captaincy, moved onto the committee and rarely appeared on the field. It was expected that Nicholls would satisfy himself by becoming a referee. But, just as it did in Australia, duty kept calling and he kept pulling on the blue and black of Cardiff and the red of Wales.

It is lucky that the Welsh Union have so capable an exponent of the Rugby code as Gwyn Nicholls to fail back upon in case of emergency. Gwyn had practically given up the game, and it is only on a few occasions that he has appeared in the football arena this season... He was, if not now, the greatest centre of the day, and one who commands universal respect, not only as a player, but as one of the best sportsmen.

Evening Express. 11th March 1905.

The emergency call up into the side for the 1905 Ireland game paid off. Wales denied Ireland the Championship and won Wales another triple crown.

Nevertheless, Nicholls had decided that his final, final game would definitely take place that spring. At his suggestion, the final game of his career would be a specially arranged charity game between East Wales and the West of England.

Nicholls then was determined to finally draw the line under his rugby career with some ceremony. He was a man who felt the need to make it abundantly clear that no matter what anyone said, his battered body would not be subjected to more “serious football”. Perhaps because he knew what was on the horizon, and the challenge that awaited Cardiff and Wales.

The New Zealand All Blacks team had been encountered by Nicholls’s clubmates Percy Bush, Rhys Gabe and Arthur Harding on the 1904 British Isles tour. Whereas they’d dazzled the Australians, in New Zealand they’d more than met their match. They lost to New Zealand and were battered by Auckland. Now the original All Black touring team were coming north.

If anyone had been in any doubt of the challenge faced by British and Irish teams, they were soon quelled by the way the All Blacks dominated all comers. In the first match, Devon (who had been favourites) were beaten 55-4. The All Blacks wouldn't concede another point for six matches. The next game against Cornwall was won 41-0. Bristol were also beaten 41-0. Northampton were beaten 32-0. Leicester 28-0. By the time Durham managed to only lose 16-3, just scoring points against the All Blacks was considered a triumph.

The team were a sensation. After sweeping aside every team in England and dispatching Scotland and Ireland, a crowd of 100,000 would watch them hammer the English national team 15-0 at Crystal Palace.

Plans were being made in Wales. The All Blacks weren’t going to be allowed to march through the Welsh clubs and annihilate the national side as they had in the rest of Britain. Bush, Gabe and the others who had faced them the previous year felt they knew how to beat them.

But they’d need Gwyn Nicholls.

Gwyn Nicholls has been invited to play and many thousands will be delighted to know that he will once again come to the assistance – one was almost tempted to say the rescue- of Wales, as he did at Swansea against Ireland, when the Triple Crown was in danger of crossing the Irish Channel in the Ides of March. Of course, there will be much speculation for some time to come as whether the doyen of Welsh three-quarters will put on the jersey again, but it may be taken as a certainty once and for all that he will make his appearance in his old position against the wearers of the silver fern.

Evening Express. 10th November 1905.

In the back of his mind, Nicholls had probably always known that despite his insistence on retiring, the appeals of his friends and old teammates would be too much to resist. The challenge of the All Blacks was too tempting. To his teammates, Nicholls was indispensable. He was valuable as a leader but also as a rugby brain. Between them, they planned and practiced moves designed to exploit the New Zealand weaknesses.

All the while, the rugby mania that followed the All Blacks around Britain drew closer. After beating Yorkshire 40-0, they made their way to Cardiff. The match with Wales would take place on 16th December, 1905.

Over 50 excursion trains will run into Cardiff on Saturday for the great football match between Wales and New Zealand, and as each train will probably bring at least 500 passengers there will be at least 25,000 excursionists seeking admission to the Cardiff ground on Saturday. Most of the excursions will arrive during the morning, and with the certainty that thousands of others will travel by the ordinary trains there is a prospect of the Cardiff Arms Park being crowded by twelve o'clock. This gives ample justification for the request that the offices at Cardiff Docks should be closed early, for if they are not the dockites will have small chance of seeing the match. On the Great Western system 29 excursions are being run from Lancashire, the Midlands, London, and all over the South of England....

... It is stated that the workmen at the Cardiff Dry Docks will be paid on Friday night, instead of Saturday, which is the usual thing. On Saturday it is probable that the men will not work later than the first quarter, or, at all events, that they will leave work by about ten o'clock. It is very likely that most of the offices will also close early.

The City of Cork Steam Packet Company announce an excursion to Cardiff via Milford in connection with the match New Zealand v. Wales.

Evening Express. 13th December 1905.

What followed was perhaps the most important rugby match ever played. In a way, every Welsh international since has been following in the footsteps of the 1905 Wales versus New Zealand game.

When the Welshmen fielded with Gwyn Nicholls at the head—he carried a gigantic leek—the applause was deafening. The Colonials sang their war song, after which the Welshmen gave a rendering of "Hen Wlad fy Nhadau”, the chorus of which went with a merry swing, with something like forty thousand voices holding forth.

The Cambrian. December 22nd 1905.

“Merry Swing” was the understatement of the century. Before an unprecedented crowd of 47,000, after watching the haka, Welsh winger Teddy Morgan stepped forward and began singing.

The other Welsh players joined in. So did members of the crowd. Soon, for the first time, 47,000 people were filling Cardiff Arms Park with the sound of the Welsh national anthem. It was the first time a national anthem was sung before a rugby or football match.

It is worth reminding ourselves of the lyrics of Mae Hen Wlad fy Nhadau.

Mae hen wlad fy nhadau yn annwyl i mi,

Gwlad beirdd a chantorion, enwogion o fri;

Ei gwrol ryfelwyr, gwladgarwyr tra mad,

Dros ryddid collasant eu gwaed.

Gwlad! Gwlad!, pleidiol wyf i'm gwlad.

Tra môr yn fur i'r bur hoff bau,

O bydded i'r hen iaith barhau.

The old land of my fathers is dear to me,

Land of bards and singers, famous men of renown;

Her brave warriors, very splendid patriots,

For freedom shed their blood.

Country, Country, I am faithful to my Country.

While the sea is a wall to the pure, most loved land,

Oh may the old language endure.

Although people had travelled from around Britain to attend the game, the bulk of the crowd that day were Welsh speaking Welshmen. On a patch of land carved out by the English engineers of the Industrial Revolution, they were now claiming the game brought to Wales by English public schoolboys as their own. Just as the New Zealanders were touring to establish themselves as masters of a game created in “the old country”, the Welsh were adopting rugby as an expression of national pride.

It was a clash between the best of Europe and the best of the Southern hemisphere. It was nothing short of a world championship. In many ways, it was the true start of the phenomenon of international rugby.

The first quarter was brutal. Witness’s years later would still say it was one of the fiercest games they’d seen. Wales gradually began to have the upper hand and were creating chances.

The first quarter was brutal. Witness’s years later would still say it was one of the fiercest games they’d seen. Wales gradually began to have the upper hand and were creating chances.

With ten minutes left of the first half, Wales had a scrum on the All Black 22. Owen, the scrum half ran to the right. Bush, Nicholls and Willie Llewellyn drifted with him and the All Black defence followed.

But it was a ploy. Owen threw a long pass left to Cliff Pritchard. Pritchard beat his man and passed to Rhys Gabe, who drew the last man and put Teddy Morgan away down the left wing.

The next moment Arthur Gould was dancing on the Press table waving his hat and shouting; “The fastest Rugby sprinter in the world! –Teddy Morgan has scored!” It may be said that in those days the Welsh Rugby Union did not know how to treat the Press; instead of reporters being given seats in the covered stand, they were placed at trestle tables inside the ropes, exposed to wind and rain, and occasionally to invasions by spectators who scaled the fences. Where Arthur Gould came from I do not know, but there he was dancing the dance of triumph.

WJ Townsend Collins, writing in 1948.

Wales were ahead three points to nil at halftime. Then the onslaught began. The All Black forwards took control and with a monopoly on possession, hammered the Welsh line for most of the second half. Nicholls led his men in 40 minutes of aggressive defence against the increasingly desperate New Zealand attacks.

Finally, the All Black centre Bob Deans broke the Welsh defence and sprinted for the line. He was brought down short and would claim to have scored. The referee said no, and Wales breathed again. A kicking duel followed, ending with Winfield finding touch in the New Zealand 22. New Zealand's last chance had gone.

The final whistle was blown.

The greatest match in football history has been fought and won by Wales. Many international matches have been classed as great games, but the struggle between New Zealand and Wales at the Cardiff Arms Park, on Saturday now claims the premier position. It was a spectacle never to be forgotten, the huge crowd of spectators and the tremendous enthusiasm shown both tended to make the occasion a brilliant one. It was the finest match I have ever had the pleasure of witnessing, and the equal of it may never be seen again.

The Cambrian. December 22nd 1905.

Gwyn Nicholls, Welsh Captain, having been carried shoulder high by his admirers to the enclosure leading to the dressing pavilion, was too full of emotion for many words.

"What do you think about it, Gwyn?" asked our representative.

"Oh," he shouted, amidst the din, "we were just as good as they were, and we seized the one chance which came to us beautifully."

"Don't you think our forwards played the true game to beat the All Blacks?"

"Yes they did; but I am too much elated just now to go into details. We won because we got the chance and used it."

Evening Express. 16th December 1905.

Six days later, the New Zealanders would get their chance for revenge on Cardiff Arms Park. After beating Glamorgan 9-0 and Newport 6-3, they would face the Blue and Blacks of Cardiff rugby club.

Percy Bush’s Cardiff side were unbeaten and included five of the team that had beaten the All Blacks on the 16th. Confidence was high.

Not for a dozen years have Cardiff had so clever a back division as this season, particularly as the three-quarter line will be strengthened to-day by the inclusion of the prince of centres, Gwyn Nicholls. At half, Percy Bush may be accepted as clever enough to outwit any opponent he may have to contend against, and R. A. Gibbs, the arch-spoiler, will be a perpetual thorn in the sides of the New Zealand backs. At inside-half R. David is very little less clever than R. M. Owen. In combined and skilful back play the Cardiff men ought certainly to be superior to their opponents. From every standpoint the prospects for Cardiff today are very rosy. The gates of the ground will be opened at 10.30 a.m., and there will be about 100 police, mounted and foot, on duty to control the crowd.

Evening Express. 26 December 1905.

The crowd that gathered at Cardiff Arms Park that day was even greater than at the international. People swarmed into the city to see if Cardiff could repeat the feat of the national side.

From an early hour the city was besieged by tens of thousands of visitors from all parts of South Wales and from more distant districts in England as well, and by eleven o'clock, when the gates of the Cardiff Arms Park were opened, there was tremendous pressure on the somewhat limited means of entrance to the ground. Excursion trains were run from all points of the compass, and the crowd, imbued with the Holiday Spirit, was even more demonstrative than that of the ever to be remembered 16th of December.

By a quarter past one the ground was so packed in all parts that the head constable advised Mr. C. S. Arthur (the Cardiff secretary) to close the gates. So closely packed were the people on the shilling stand that there was an absence of that dangerous swaying which threatened so much danger on the occasion of the international match.

Evening Express. 26th December 1905.

Nicholls would score the first try of the game after being put through a gap by Gabe. But the match was tied 5 all at halftime. In the second half, Cardiff were in the ascendancy and narrowly missed several chances to score, before Percy Bush made the mistake which would haunt him for the rest of his days.

With the ball practically in his possession over his own goal-line, he dallied with it, when a child might have touched it down by simply putting one hand on it, and the next moment he found, to his mortification, that a New Zealand forward had dashed up and scored a try.

Evening Express. 27th December 1905.

The softest of tries had given the All Blacks the lead. Cardiff would continue to create chances but the All Black defence was as aggressive as the Welsh defence had been a week before. A late try for Ralph Thomas in the corner made the score 10-8. But Winfield's conversion to draw the match narrowly missed.

It is doubtful whether the Colonial defence has ever been so thoroughly beaten as it was by the scoring of this second try— every man in the Cardiff back division handling the ball, and Ralph Thomas putting on the finishing touch by bounding over in the corner. This try, as I have already remarked, fully deserved to save Cardiff the game, but the fortunes of the day were on the side of the Colonials.

Evening Express. 27th December 1905.

The Cardiff versus All Blacks match of Boxing Day 1905 remains the great "What if?" of Cardiff rugby history. In many ways, the performance and the occasion exceeded that of the international match. No-one else scored as many tries against New Zealand. But Cardiff nevertheless lost a match they felt they should have won.

But the story wasn't yet over.

Sport history is full of great figures whose reputation rests on one great day. The greatness of Gwyn Nicholls is that he had more than one day which is written into rugby history.

The following year, another formidable touring team would head for the British Isles. The first Springboks, like the All Blacks, caused a sensation. Nicholls once again came out of retirement to captain Wales against the tourists. But this time, age seemed to be catching up with him. South Africa won 11-0 at St Helens in Swansea and it was to be the last appearance in red for Nicholls and several others.

After the game, the South Africans were dismissive.

Some of the Welsh team are magnificent players, others well, they ought to have retired long ago. Take Gwyn Nicholls. Five years back he was one of the best men in England. Today he is not. Younger men have come into the field. Football is essentially a game for young men.

Springbok Centre Japie Krige quoted in the Evening Express. 15th December 1906.

Marsburg said that he had seen Gwyn Nicholls playing against the Barbarians on Boxing Day, and that he admired his play greatly. "But," he said, "you ought to have seen Krige playing in 1898. He used to run through every team he played against, and score in every match. But Nicholls, judging him on his form on Boxing Day, must have been a wonderful player in his best days."

Evening Express. 29th December 1906.

A month after the humiliation in Swansea, Nicholls would face the Springboks once more. On New Year’s Day 1906 they faced Cardiff at the Arms Park.

History doesn’t record whether Gwyn Nicholls read the newspapers, or the interviews that wrote him off as being too old. What history does record is that on the night before the game, Percy Bush was woken by the sound of heavy rain falling against his bedroom window. Looking outside to see the Welsh rain pounding the city streets, he thought of the effect the rain would be having on the clayish Arms park soil and how different it would be to the hard, dry pitches of South Africa. Advantage Cardiff. Percy Bush slept soundly that night.

What followed was what remains perhaps the greatest win by a club team over any international team.

Early on, Nicholls carved through the Springboks to open the scoring with a try. Three more followed for the Blue and Blacks as Cardiff beat the South Africans 17-0.

Yesterday the capital of Wales made history by coming to the rescue of national prestige, and Cardiff, to the lasting credit of the club, inflicted such a defeat upon the Springboks as to rehabilitate Wales in the eyes of the whole sporting world. In that defeat there was not the slightest suggestion or semblance of flukiness or of luck. It was decisive; it was thorough; it was complete; it was triumphant.

Evening Express. 2nd January 1907.

In the Cardiff Arms Park mud, Gwyn Nicholls at the age of 31 had played his greatest game. A career which might have ended 8 years earlier rough riding in Australia, had brought Gwyn Nicholls victory over the All Blacks and now the Springboks. In the Red of Wales and now in the Blue and Black of his beloved Cardiff, he had beaten the world.

Perhaps in the pavilion after that match, as they sat in their muddy blue and black jerseys, there would have been a knowing look between Nicholls, Winfield, Gabe and Bush. The men who had beaten the All Blacks and now the Springboks. They must have known that the cheers at Cardiff Arms Park that day would follow them for the rest of their lives, and beyond. They had made themselves immortal.

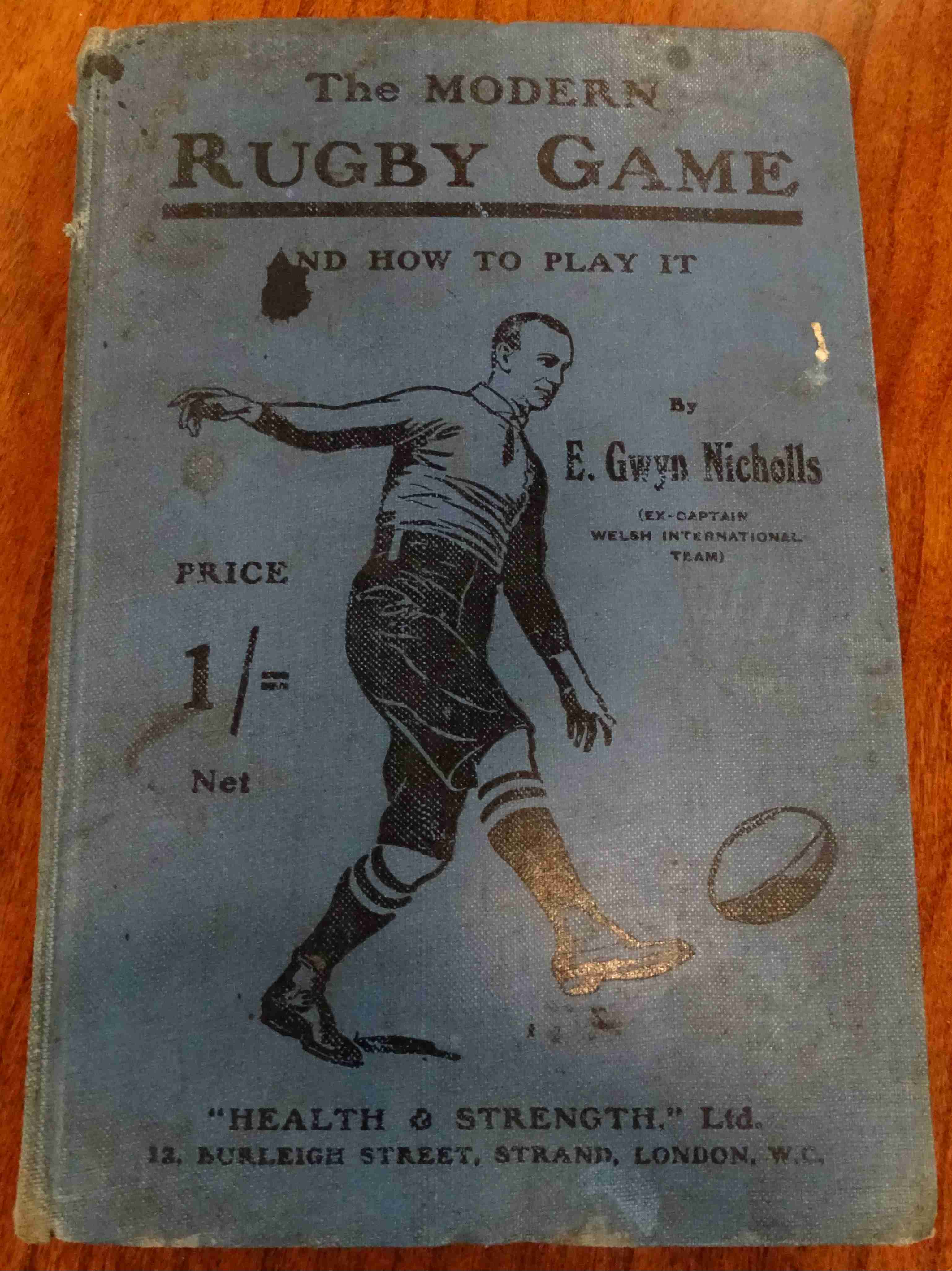

The following year, Nicholls published “The Modern Rugby Game and How to Play It”. A manual describing his approach to the game. One of the first of its kind. He served on Cardiff’s committee and now and again would return to the field. He settled into life as a businessman and a grandee of the sport.

On 18th August 1923, three girls from St Joseph's Training School in Bristol waded into the water at Weston Bay on the Somerset side of the Bristol Channel. The calm surface of the Bristol Channel hides powerful undertows. Like countless others, they found themselves being swept out to sea.

They were spotted by a man of 49, 6 feet tall, greying and unquestionably brave. Gwyn Nicholls strode into the swirling water and swam out into the current to save them.

He was soon joined by a second rescuer, Dr Edward Holborow and a third, local lifesaving instructor Henry Harris. The three girls survived but despite Harris hauling Holborow back to shore on a lifebelt, the 37 year old doctor died on the beach. Nicholls himself barely made it back to shore alive after fighting against the undertow.

It’s said that Nicholls never fully recovered from the ordeal. But it took another 16 years for him to pass away. He died in Dinas Powys in 1939. He was 64 years old.

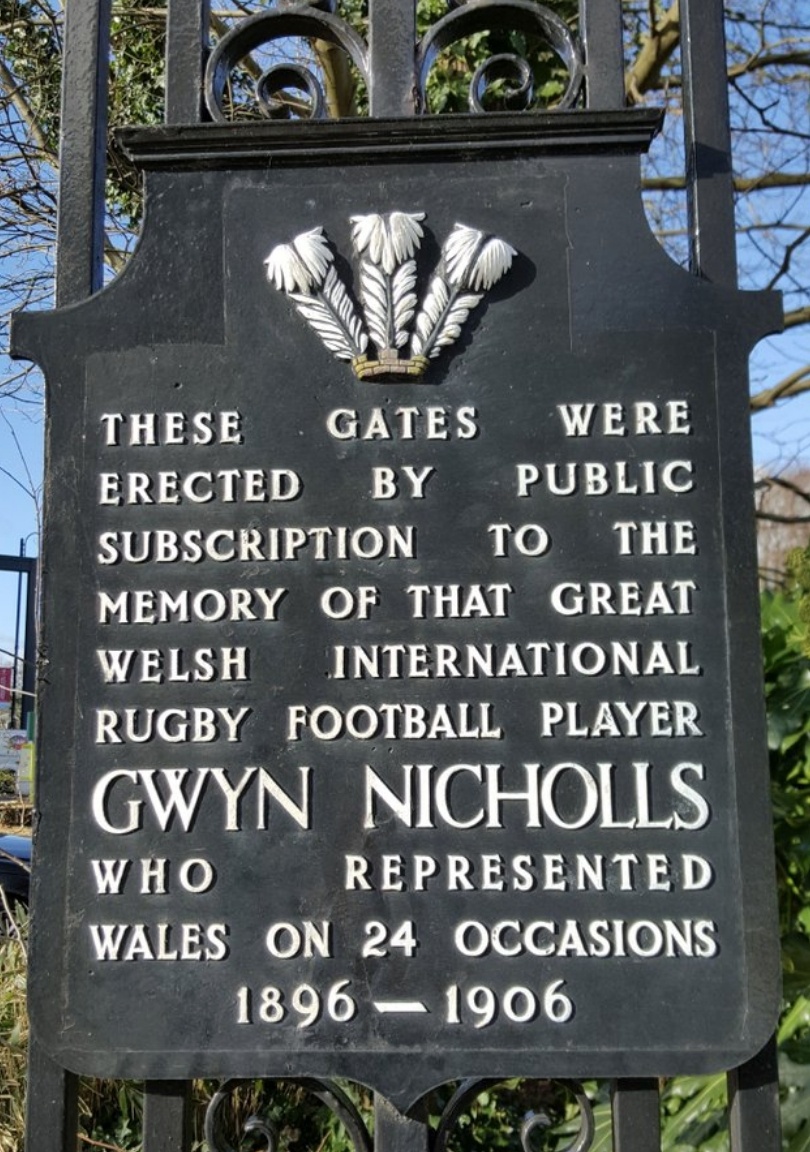

Almost immediately, there were calls for a public memorial. After World War II had ended, those calls weren’t forgotten and, paid for by public donations, the Gwyn Nicholls gates were erected at Cardiff Arms Park.

It’s a measure of Nicholls’s influence that 42 years after his final triumph at the Arms Park and 55 years after his Cardiff debut, that the people of the city while recovering from a World War, prioritised building him this monument.

The Gwyn Nicholls gates still stand at the Angel End of Cardiff Arms Park. On match day thousands walk through them, likely without a second thought. Once located at the Quay Street entrance, as the main entry point to the Arms Park, they are now almost always open to allow the flow of traffic into the car park. Their grandeur is disguised. The plaque commemorating Gwyn Nicholls himself is rarely read.

But in truth, perhaps Gwyn Nicholls’s monument isn’t simply those gates, but Cardiff Arms Park itself. Gwyn Nicholls was the first true superstar of Cardiff rugby. He will always be special. He more than any one player built the reputation of Cardiff Arms Park and Cardiff Rugby.

There were certainly others. Others have followed in his footsteps, and others preceded him. But when you consider his perfection of the Cardiff passing game created by Frank Hancock, and add to it the seismic events of 1905 and 1907, arguably no other player can quite match his impact. When you walk through the Gwyn Nicholls gates, you are entering not just the place where he played but the place he helped build. You are entering what will forever be His house.

Percy Bush, Rhys Gabe and the others, we salute you. But most of all we salute the immortal Gwyn Nicholls. Prince of centre three-quarters. He is the best man breathing.

“How Wales Beat the Mighty All Blacks” – A children’s book by CF10 member James Stafford retelling the story of the historic 1905 match is out now.

https://www.ylolfa.com/products/9781800990340/how-wales-beat-the-mighty-all-blacks

Illustrations from “How Wales Beat the Mighty All Blacks”

Photographs courtesy of The Cardiff Rugby Museum

Comments

Leave a Comment

Get Involved

If you liked this piece and want to contribute to the independent voice of Cardiff rugby then you can join us here. As a member led organisation we want to hear from you about the issues you want us to raise.

Thank you so much for writing this article.

Gwyn Nicholls was my grandfather. I am the daughter of his only daughter Erith.

I live in Canada now, but I still like to boast about him here, because I am so proud to be his granddaughter and I want people to know about him.

This article will help me do it!